Sad Girl Indie

Algorithms and algorithmically-informed fan cultures are reducing today’s most popular women-songwriters to “cry-now” buttons

This past Saturday I had the privilege to attend a Mitski concert in Montreal while on spring break. To contextualize, I am not, as they say, a Mitski stan. My friends and I were there to support her opener, the great band MICHELLE, some of whose members I’m friends with from school (please stream their great new album by the way!!).

But I do like Mitski and particularly loved her breakthrough album Puberty 2 when it came out. I have always admired her melodic experimentation, how she shiftily and stubbornly avoids straightforward tonality, and her lyrics always balance poetic impressionism with an evocative narrative tether. She’s one of today’s best. But frankly, sometimes listening to her is too much for my little aching heart. The feelings her music evokes for me are so visceral and hard to name that I tend to avoid actively listening to her music as a part of my regular listening practice. So to end up in this room, with thousands of her most adoring fans who waited all day to get inside the venue and claim their territory near the stage, who jumped through hoops to get those fast-selling tickets, was strange to say the least.

Once Mitski got on stage, it was one long karaoke session. The crowd was incredibly young, probably averaging at 21 or younger, presented femme and queer, and they knew every word, every breath of her music. On stage, Mitski moved in a similar way to how she does in her videos, dancing in long, trembling motions, using her arms and hands to paint the air and grace her face with the onset of a melodic climax. She was quiet in between songs. She barely, if ever, bantered. But that’s not the kind of artist she is. She is not her audience’s friend, but their conscience. The gaping wound with which they are able to feel their own pulsing hearts. I didn’t see so much dancing as I did wavering. Not so much exaltations as quiet exorcisms.

It is now a bit of a cliche online that Mitski’s fans cry to her music. Mitski’s popularity has risen in the past two years as her music has become increasingly used on Tik Tok, usually by young fans who use her songs as a background accoutrement to whatever extreme moment of sadness they are depicting. In a recent profile of Mitski for the NYT magazine, Lindsay Zoladz digs into the variables that have made her the “high priestess of modern-day sadness” to many, but particularly her Gen Z fans. Zoldaz describes MitskiTok as a place where fans “exaggeratedly aestheticize feelings for which they may not have other outlets.” While there’s an undoubtedly deep emotional connection that Mitski’s fans have with her, the extremity of their displayed emotional relationships with her cannot be disentangled from the technologies that mediate them.

Mitski, who is generally ambivalent to her public perception, even commented on her role as a Tik Tok phenomenon. Speaking broadly but surely referring to her own impression of Tik Toks that use her music she says, “I am always surprised that there seems to be a complete freedom of disclosure about people’s very private things. There seems to be this utter nihilism with Gen Z. They’re exposing these vulnerable things, but there is no sense of ‘exposing this will hurt me,’ because ‘nothing can hurt me.’”

As a Gen Zer and a, um, Tik Toker, Mitski’s millennial take strikes me as deeply true. I know firsthand that Tik Tok encourages the performance of extremes. Indulge me for a moment: this little blog you’re reading has grown its readership through Tik Tok in the last few months. The strategy has been very simple and effective. Everytime I post an article, I also post a Tik Tok alongside it with the most reductive, inciting version of my article possible written in text-form atop my face in the background. Behind the video is music that vibes with the general music/topic I’m discussing. The short length of the video and the long length of the text forces the viewer to loop the video, which boosts it in ~the algorithm~ and the inciting rhetoric prompts people to respond in the comments which also, you know, boosts. I’m explaining this because as a reader of this article you can hopefully tell that I am at least thoughtful, and yet I have also realized that presenting a sort of clownish caricature of my perspective serves me in a very real way. Writers and musicians I have admired for years have read this blog because of my actions on Tik Tok! The algorithm, and the world, is begging me to make a fool of myself.

With this in mind, those Tik Toks featuring fans having cry-spirals to Mitski’s music are informed by an intuitive understanding that extremity does well on Tik Tok and they will likely be rewarded for their excessive performance. They are also taking part in a trend. Crying, freaking out, throwing up and shaking to Mitski is a meme, so if they participate in the meme-spectacle they are more likely to show up on other people’s For You Page who tend to like that sort of thing. All of this works to simplify and instrumentalize Mitski’s complex music into being understood as basically “sad.” And that’s a disservice to the nuance of her art. Take it from the artist herself. Speaking to Zoldaz, she relents: “The specific kind of pain that is asked of me is the sort of screaming, most expressive, outgoing, adolescent pain. There’s all sorts of other pain. There’s a grown-up, fatigued pain as well.” Mitski correctly intuits that the sad service she is fulfilling is not sadness writ large, but a caricatured one: sadness through an algorithmic prism. Sadness turned to 11.

All of this makes me think of Spotify’s 2019 campaign, “music for every mood,” which sought to exemplify the various ways that Spotify’s plethora of editor-curated playlists can be deployed to deepen, alter, or provide ambiance for the many situations Spotify users find themselves in. The premise of the ad campaign was telling for how Spotify thinks of music: music is for the background of whatever situation its users find themselves in. The “for” in the slogan implicitly intstrumetnalizes music and turns it into a service of a moment, a feeling.

And maybe that’s an intuitive understanding of music for many, but I think most music fans have the nuance and taste to also understand that a lot of music, and a lot of our favorite music, does not have as simple relationship to mood as this ad campaign implies. Yes, we have our “cry songs,” but we also have those songs we return to again and again because we love them, we find them perplexing, we don’t know how they make us feel, and that enriches our life.

When I listen to Mitski, the music does not sound just sad to me. It sounds powerful, painful, deep. Maybe to others, Mitski is simply their go to cry-jam, but to shove her whole discography into that small bucket feels really shortsighted to me, and apparently to Mitski as well.

It seems that this rush to instrumentalize certain artists into quick cry-fixes is particularly relevant for women-songwriters/singers who, yes, are incredibly vulnerable and open in their music, but by no means make music that is so simple that it can be cleanly and easily relegated as “sad.” Artists like Phoebe Bridgers, Japanese Breakfast, Snail Mail, Lucy Dacus seem to all evoke this sort of parasocial instrumentalization where fans on social media characterize their music as emotional outlets they turn to for sobs. And like, great, get your cry on! But does anyone else think it’s strange that it falls suspiciously on the shoulders of women-songwriters to become this endless void of pain in which the world can feel through? Maybe these artists, who devote years to crafting their music and output, deserve a little bit of a more nuanced reception than “it’s cry time??

There’s a dialectic emerging here. Yes, it’s between artists and their fans. And yes, fans will inevitably will misunderstand the artists they adore in crucial ways. But between artists and fans, there is also technology.

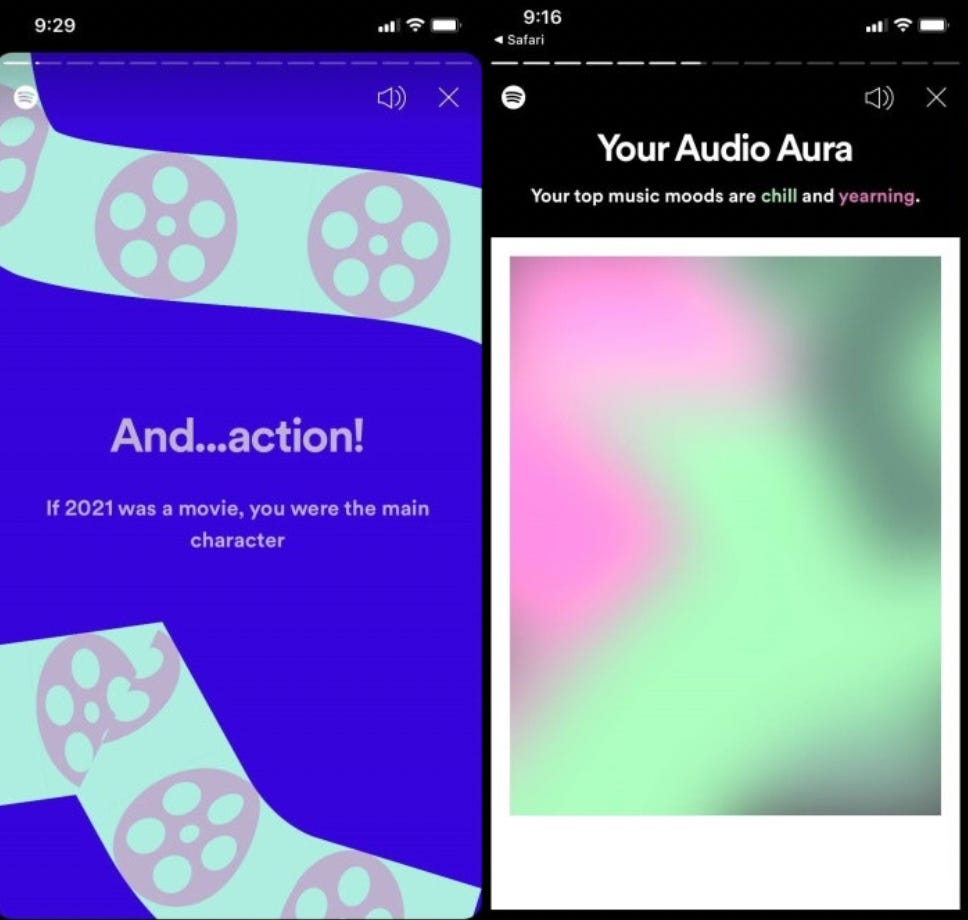

There’s the streaming platforms like Spotify who recommend music via mood through their popular mood-based playlists, selling a very narrow idea of music. And they also hock this idea through their incessant branding exercises, like uuuum, telling you what your aura is based on your listening habits as part of their yearly Spotify wrapped feature. Through constant signals, Spotify naturalizes the idea of a supposedly easy connection between mood and music.

And there’s Tik Tok, which encourages over the top emotional performance to maximize engagement. To do well on MitskiTok, fans are encouraged to perform sadness in the most extreme way possible. Putting this together with the idea of mood-music that streaming platforms are selling, you get extreme mood-music. Music in service of a moment, but that moment is commodified for attentional platforms like Tik Tok and thus these emotions are performed so excessively that mood becomes not just affect but indulgent collapse. Then you sprinkle on a societal disposition towards simplifying women-artists into femme-fatals, into broken heroine geniuses, into manic pixie dream girls, and you get . . . well, this!

I’m glad that some of these technologies have come together to help artists like Mitski and Phoebe and others that are making genuinely interesting, moving music, but I wish that the nuanced edges of their art didn’t get so sweeped away in the emotional-algorithmic shuffle. What I hope is that over time, we can let the music sink in, move through us, before we box it in so simplistically.

If this article resonated with you and you feel so inclined, consider paying a small tip via Venmo @tobiasfornow or Cash App $tobiasfornow. Writing these articles takes a lot of time and deep effort and any support helps give me more time to write and produce the best criticism I can. Thank you to all of you who read, share, and subscribe! It’s beyond heartwarming to hear your responses. Oh, and don’t forget to subscribe!

Brava!